Online Disinformation in Europe

Last year, we had the opportunity to conduct a desk research study in an effort to map the landscape of online disinformation in Europe. Our research was guided by three research questions:

- What are the measures and journalistic authorities in Europe that supervise and monitor the ethical application of journalism?

- Are there patterns of false information spreading as a means to serve the agenda and interests of certain political groups? Are there certain political groups that benefit as a result of given disinformation narratives?

- Are there specific and tangible policies that have been proposed by European and international organisations that could help tackle online disinformation?

To make the study of the first two questions more manageable, we focused on five European countries: France, Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain, and on three topics that are commonly associated with disinformation: COVID-19, immigration, and climate change. The resulting report is available here and we believe it could be valuable for informing a number of stakeholders, including professionals in the media industry and policy makers. In the following, we try to present the key insights that we managed to draw from this report.

What are the measures and journalistic authorities in Europe that supervise and monitor the ethical application of journalism?

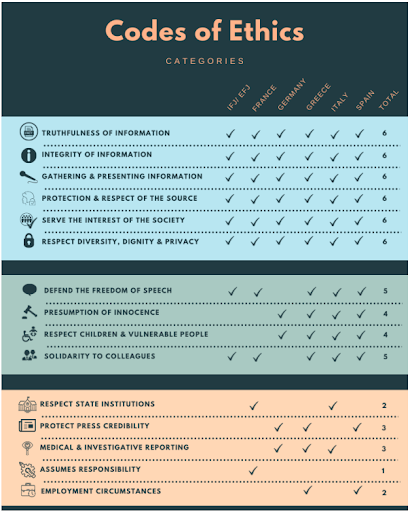

The primary organizations overseeing the application of ethical standards in journalism in Europe and worldwide are the European Regulators Group for Audiovisual Media Services (ERGA), the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) and the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). European countries follow their own national codes of ethical conduct, though there are certain commonalities across the conducts (cf. figure below) and truthful reporting is among these common principles.An additional important reference document in Europe is the Code of Practice on Disinformation, which includes relevant commitments on behalf of social media platforms and internet advertising companies. Finally, our study points out that complying with ethical standards is increasingly challenging for news organizations and journalists due to the 24/7 news lifecycle, the reliance on Internet advertising as a primary source of income and several other factors that affect media independence and plurality. Yet, failure to comply with ethical standards is found as a reason for the reduced trust of citizens in the media.

Are there patterns of false information spreading as a means to serve the agenda and interests of certain political groups? Are there certain political groups that benefit as a result of given disinformation narratives?

Among the three topics of focus for our study, disinformation was prevalent with respect to COVID-19 and immigration and much less pronounced with respect to climate change. At an EU and national level, we found evidence that COVID-19 related disinformation more often originates or is disseminated by far-right wing parties and politicians, while at an international level disinformation campaigns targeting European citizens appear to mainly originate from Russia and China and primarily target Germany and Italy. On the topic of immigration, we could identify several disinformation activities, featuring anti-immigrant narratives and sentiments, racist and xenophobic attitudes that were aligned with the agenda and ideology of far-right and rightwing parties, and sometimes pro-Kremlin media amplify the messages of far-right politicians (e.g. in Germany); however, there is no evidence of any kind of cooperation or coordination between them. On the topic of climate change, there seems to be a shift from climate change denialism to skepticism, but in general it appears that European countries are not fertile ground for climate change disinformation.

Are there specific and tangible policies that have been proposed by European and international organisations that could help tackle online disinformation?

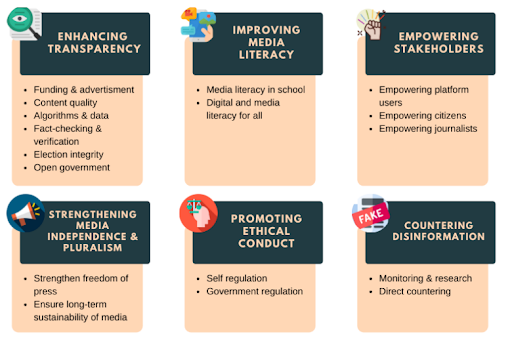

There are already a number of reports that recommend concrete policies and measures with a view to mitigating the effects of disinformation and limiting its root factors. Our analysis of existing recommendations highlights that the phenomenon of disinformation cannot be addressed with fragmented, one-dimensional or simply regulatory policies. It calls for a multi-dimensional, multi-faceted, multi-stakeholder policy framework that assigns fair responsibility to and requires decisive action from all relevant stakeholders. In particular, we present a six-dimensional policy framework (cf. figure below) that could be a useful reference for discussions among policy makers and other stakeholders. The recommended policies are organized in the following six dimensions: a) enhancement of the transparency of the digital media ecosystem; b) cultivation of media literacy and digital skills in different groups of citizens; c) empowerment of different groups of stakeholders, including platform users, citizens, and journalists; d) strengthening media independence and pluralism; e) promotion of ethical conduct in media, journalism and platforms; and f) support of independent research on monitoring the disinformation phenomenon and building services and tools for countering online disinformation.

The report was co-authored and researched by Ms. Georgia Pantalona, Dr. Filareti Tsalakanidou, Dr. Evangelia Kartsounidou, Dr. Symeon Papadopoulos, Dr. Nikos Sarris and Dr. Yiannis Kompatsiaris. The study was commissioned by the Left group in the European Parliament – GUE/NGL. To ensure the objectivity and transparency of the research, our research team conducted the study in a fully autonomous way without any intervention by the EP members. We made every possible effort to avoid expressing directly or indirectly any personal opinion or stance by the authors in this document and therefore we limited ourselves to analysing, synthesizing, summarizing and interpreting conclusions and evidence from primary sources. Last but not least, the researchers involved in the execution of the study have no direct or indirect association or affiliation with any political party or fraction. In addition, they have no further benefit or dependence on the content and conclusions of this study.

The content of this post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).